Ki is universal energy, pronounced Qi in Chinese.

Our body can survive without eating for weeks, without drinking water for days, but if we cannot breathe our body will die in a few minutes.

I suffered with asthma throughout my childhood and couldn’t exercise at anything closed to high intensity without wheezing and reaching for my inhaler. I didn’t go anywhere without it. Every year it was getting worse too, and in my early thirties I found each winter a simple chest infection would become debilitating and I was prescribed steroids to get through it.

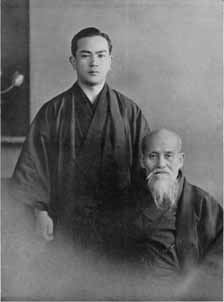

I had been training in Aikido though and for my shodan (first dan) grading I was required to write an academic essay on Aikido. I researched the lives of the founder of Aikido; Morihei Ueshiba “O’Sensei”, and the head of our style of Aikido Koichi Tohei.

I was startled to read that Tohei Sensei too had struggled with poor health during Aikido training with O’Sensei. Tohei had also studied Zen, Yogo and meditation and had learned a primitive form of whole body breathing where each breath, in and out would extend for up to one minute.

When war service interpreted his Aikido training he vowed to practice three hundred breaths each day for one year.

If he missed a day he would do double the next day to make them up

I did not set my own goals that high, not even halfway. I decided to practice thirty breaths a day.

My Sensei (Stoopman) had taught us about Ki Breathing, explaining that our lungs were like a stagnant lake; full of foul water that could not sustain life. But that if a little of the foulest water was replaced with fresh water each day then over time the lake would be returned to health.

Thirty breaths a day, how hard could that be? I thought.

It was hard. Whatever you’re thinking, it was harder than that. Ki breathing is not just sitting in seiza and drifting off, there was true physical pain. The first breath is slow but as they became longer my lungs screamed as I pushed my diaphragm to expel every milliliter of air from my lungs, when every instinct in my being called for me to suck air in. And when filling my lungs, stretching them beyond their capacity, all I wanted to do was breath out again.

Progress wasn’t slow, it was non existent.

I kelp a register though and once missed ten days straight, that meant double effort for another ten days just too break even. I only let it slip that far once. After several months it became my nightly or early morning habit but I still hadn’t noticed any progress.

That’s the thing about breathing, you don’t notice when you’re doing it right.

Over a year and a half later I returned from a business trip and found my inhaler on the ground under my bed. I had forgotten to even take it, let alone think to use it.

This was an empowering feeling, one you may only understand if you had also been reliant on a similar device for relief of symptoms or pain. I told everyone, including my skeptical doctor. She tested my lung capacity and it had increased, not to a healthy level but it was a improvement. But my success distracted me and I let a few days slip past and then a few weeks and then at work one day I was ruffling through my desk draw looking for that damned inhaler.

What I’d been told many times but failed to understand was that it was a healthy process I should strive for, not a cure.

I’d stalled the cleansing process at the first sign of life and it had not taken long for the rot to set back in.

So I made Ki Breathing a part of my life, not looking to cure my asthma but to dilute its symptoms one breath, one day, at a time. Now many years later I haven’t had any asthma medication for more than ten years and have almost forgotten what it feels like to be short of breath or wheeze, even doing lactate threshold training (vomit training) on my bike at nearby Mt Coot-tha.

Now my lungs are like a healthy lake, full of fresh clean water, and even if I get a chest cold it is like a drop of foul water in the ocean (…lake) and is soon dissipated without a trace.

Enough testimonial, how do you do it!

- Position yourself in the correct seiza posture; or on a chair with mind and body unified leaning slightly forward over your centre; knees about two fists apart. Place both hands lightly on the thighs with fingers naturally pointing downward. Straighten the sacrum and relax the whole body while bringing the mind down to the one point or hara. This is the neutral position. Concentrate and imagine your mind at your centre. Allow your muscles to naturally relax but not collapse.

- When you have inhaled all that you comfortably can, you are ready to begin… Close your eyes gently, mouth slightly open and start to exhale calmly, as if saying ‘ah’ without using your voice. Maintain the same sitting posture while exhaling. Imagine breathing out completely emptying your body, right down to the toes. When the breathe has naturally expired, incline the head and body slightly forward visualising your breathe still travelling out. Exhalation should be about 15-20 seconds at first, tilting the body, visualising your continued breath for about 5-8 seconds. The exhalation process should be from the chest first, then the abdomen, the inhalation process is the reverse, breathe into the abdomen first then into the chest.

- Inhaling – keeping the same posture as the finished exhalation position, close mouth and being to inhale calmly through the nose with a smooth, relaxed sound. Imagine filling your body with clean air gradually from the toes through the legs, abdomen, and chest for about 15 seconds. When the chest is naturally full (without raising your shoulders) return the upper body to the original position for a duration of about 5 seconds, the whole time visualising your breath still entering your body. Your head should return back to the neutral position calmly. Note: Do not over-stretch the chest or lean back too far when returning to the original position.

Start with shorter breaths and lengthen them a little with each breath. When they are longer don’t be alarmed to hear the crackle of flem as you expel the last bit of air from the deepest reaches of your lungs, savor this as it is clearing parts of your lungs that have not felt fresh air possibly since your birth.

"Mind and Body Are One", calligraphy by Koichi Tohei Sensei

Tohei Sensie passed away last May at the age of 91. Here is a link to the official website for his Ki Society Aikido.

Note: The Ki calligraphy at the top of this post was painted by Shodo master Kojima Sensei at a demonstration he gave at an Aikido Seminar in Brisbane Australia in 2005.